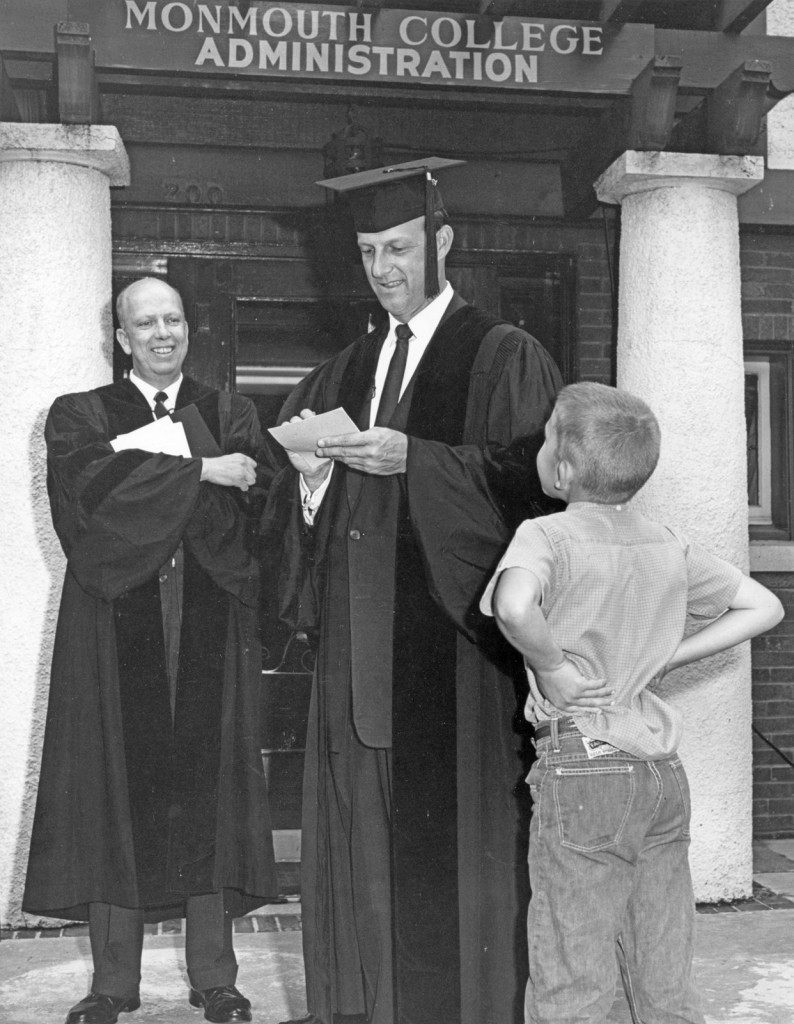

Musial signs an autograph in front of the administration building. The young fan is Dave Behnke, son of Dottie Behnke ’49 and the late Gene Behnke ’51. Looking on is Thom Hunter, another honorary degree recipient at the 1962 commencement.

On a warm Monday morning in June just over half a century ago, an overflow crowd in front of Wallace Hall watched members of the Class of 1962 receive their degrees, yet many of the spectators were there not so much to honor the graduates as to catch a glimpse of the future Hall of Famer. “Stan the Man” was one of six distinguished men selected to receive honorary degrees that day.

Yet the decision to honor a baseball player hadn’t been without controversy.

The nomination had come from the Rev. Dan Long of Rock Island’s Broadway Presbyterian Church, a member of the college’s nominating committee for honorary degrees. “This isn’t just a publicity stunt,” Long told a reporter. “It started when our chairman suggested that we broaden our field in the awarding of special honors. It was felt that in the past we had stuck too closely to the ecclesiastical field, and the idea now is to make our awards symbolic of the entire American way of life. In other words, sports represent something important to Americans, as do religion, education, art, science and politics. We want people to recognize that fact, and, since one of the purposes of an educational institution is to place emphasis on the higher values, nothing could be more fitting.”

Other athletes considered for a degree included Warren Spahn, Gil Hodges and Bob Friend, but they were rejected for not having the same level of community and philanthropic involvement as the Cardinal slugger, who during the off-season remained in St. Louis, where he was active in community life, serving such projects as Easter Seals. “The committee took cognizance not only of his tremendous achievements as an athlete, but more particularly of the example he has set for young people in his personal life,”Long said.

John Niblock ’58, a young director of publicity for the college, had the unenviable charge of getting national press coverage for the college, while deflecting criticism that Musial’s degree was nothing but a publicity stunt. Even locating a publicity photo of Musial in a business suit rather than a baseball uniform proved a challenge. Niblock finally contacted Musial’s restaurant in St. Louis, which with some difficulty located one in the files.

In days before electronic communication, what today would be a routine task of getting photos and video to news outlets required a bit of creativity. “AP wanted a photo of Stan getting hooded for his doctorate, but needed it before the actual commencement took place later that day,” Niblock recalled. “So we staged it there at the podium at Wallace Hall and they ran it with the headline, ‘Musial’s Monmouth Warm-Up,’ to indicate it was not the actual ceremony. Later, another media request–WOC-TV or WHBF-TV wanted color film of the ceremony with Stan the Man, and we shot it and sent it by courier to the Quad-Cities so they could work it into the evening newscast.”

Niblock said his student photographer, Phil Krebs ’64, shot the film in 8mm, which the station had to copy into a 16mm format before airing it on the evening news.

Also on the docket for receiving honorary degrees that day were the commencement speaker, Philip Coombs, assistant secretary of state for educational and cultural affairs; H. Stanley Bennett, biology dean University of Chicago Medical School, David Dodds Henry, president of the University of Illinois; Norman Hilberry, former director of Argonne National Laboratory; and the Rev. Thom H. Hunter, vice president of McCormick Theological Seminary, making some college officials nervous about how Musial’s presence would be received.

Any fears that Musial wouldn’t measure up were quickly allayed, however, as the humanity, humility and genuineness of the baseball star were immediately apparent to all who encountered him.

Musial, who wrote later that “It takes a man like myself who didn’t get one to appreciate a college education,” had just driven to Monmouth from the University of Notre Dame, where his son Dick had graduated the previous day. His pride in watching that ceremony, so quickly followed by the Monmouth College honor, made it an emotional day for him, but one in which gratitude shined through. Jim Lodwick, a former Monmouth resident, related a story about his mother-in-law’s encounter with Musial at a local drugstore: “As she was entering, this gentleman held the door for her and inside they chatted while waiting for service. She did not know who the man was but later found out that it was Stan Musial.”

MC’s late director of development David Fleming ’46 arranged for Musial to sign a batch of baseballs for college staff, which he cheerfully did, as well as supplying many other autographs that day.

Beyond the considerable media hoopla, the ceremony conferring of Musial’s honorary doctor of humanities degree was framed in dignity. In presenting Musial for the degree, the inimitable biology professor John Ketterer said, “Such is his prowess that even the vociferous partisans of Flatbush gathered within the sacrosanct walls of the late lamented Ebbetts Field found naught but to praise and dubbed him “Stan the Man.”

In addition to pleasing the commencement crowd, the day proved successful from a PR standpoint, as each of the seven New York City papers carried a story about Musial’s honor the next morning and it even made Time magazine. According to Niblock, “We had a shot at getting a photo in Life magazine that week, but got crowded out by Kennedy’s foreign policy speech urging peace in a nuclear age at the American University commencement.”

Not everyone, however, was impressed. Charles McCabe, the crusty columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle, charged that Musial had “cheapened himself just a bit” accepting a degree from “a jerkwater Illinois College.” He added that“Baseball is too decent, too pure, too inspiring a thing for our youth to be exploited by a lot of frustrated experts on Phoenician Maritime History or the sprung rhythm of Gerard Unmanly Hopkins.” To add insult to injury, the Cincinnati post ran a story saying the degree was conferred by Monmouth College of New Jersey.