At the final NARU graduation ceremonies in 1945, Navy Lt. Merlin Shultz presented a special citation and award to President Grier.

(Conclusion of a three-part series)

For 30 months Monmouth College had shared its facilities with the Navy and during that time more than 4,000 men received training. As the war began to draw to a conclusion in the spring of 1945, it became evident that the college was receiving more applications for admission than it had space to assign. After some conversations with Washington, the Navy made arrangements to vacate the dormitories by mid-summer, thus providing rooms for 180 more young women.

On July 24, the final NARU graduation ceremonies were held in the Auditorium and President Grier was presented with a citation from Vice Adm. Jacobs for the college’s help with the war. Remaining undergraduate platoons were moved to Muhlenberg College in Pennsylvania. It was estimated that the Navy experience at Monmouth resulted in a cool million in additional revenues to the financially-strapped college.

On Dec. 7, 1945, four years to the day after the United States was drawn into the war, the Monmouth College Athletic Board awarded honorary M Club membership to a notable Fighting Scot. That man was the former Supreme Allied Commander of the Southwest Pacific theater, General Douglas MacArthur. In a letter of acceptance, MacArthur wrote President Grier: “I am very grateful to be identified with so noble a group and shall hope at some future time to express in person my pleasure at being one of them.” News of the award was published by the Associated Press, United Press and Stars and Stripes.

In July 1946 college presidents met in Cleveland to discuss the problem of accommodating the waves of returning veterans. According to president Grier, they were haunted by two monumental questions: what to do with the atomic bomb and what to do with all the students. “Most of us are little concerned personally with the former problem,” Grier reported, “but much with the second.”

And there was reason to be concerned, as the new G.I. Bill brought veterans back to campus in unprecedented numbers. College trustees had recently approved construction of a new dorm, Winbigler Hall, but by the fall of 1946, the 68 girls assigned to the building discovered the rooms still had no doors and the only furniture was beds.

Rotary Hall, which would later form the west wing of Fulton Hall, was constructed next to the Phi Kap fraternity house with donations from the local Rotary Hall to house returning veterans.

With virtually no private housing available in Monmouth, the local Rotary Club was made aware of the problem and rallied with a major fund drive to construct a residence hall for 34 men. Known as Rotary Hall, it would later become the rear wing of Fulton Hall. However, because it was far from complete, the 34 future residents spent most of their first semester living in the college gymnasium. Finally, the students were enlisted to paint their new residence, and as a result, were allowed to move in on November 22—two to four men sharing each room.

Thanks to the Federal Public Housing Authority, housing for married veterans was also made available. Eight apartments were hastily constructed on North Ninth Street, and finished just after Christmas 1946. Each efficiency apartment had all the comforts of home—kitchen, bathroom, living room, bedroom, gas space heater. Making the living arrangements all the more challenging was the fact that five of the eight couples had small children.

After the Navy moved out, women on campus reclaimed their dining facilities in the basement of McMichael Hall.

Back in the McMichael Hall dining room, which had been reclaimed from the NARU cadets, women now took their meals and etiquette was the name of the game. Grace was sung, posture was erect, serving dishes were passed in the correct direction and all waited for the upper class girl at the head of the table. Group singing between courses led to very lengthy dinners. According to one of the underclass girls, Louise DuBois Kasch ’48, she and Helen Wohler Tourney ’48 would on occasion decide to depart early and crawl on hands and knees the length of the dining room to escape from the south door undetected. Other times, she would have a violent coughing spell, needing assistance from her co-conspirator in leaving the dining room.

Some of the returning veterans were actually ex-Navy cadets, who had fallen in love with Monmouth during their training days and decided to return. One such cadet, Red Poling, would later see his name gracing the former college library. The future CEO of Ford Motor Company never forgot his Monmouth education and served the college with distinction as a trustee and major donor.

A priority for the returning vets, who were much more worldly and needed a place to unwind from their studies, was the establishment of a student union. The Alumni Association passed a resolution to designate the entire annual fund for 1946-47 to this cause. Many other fund drives were started, and proceeds from Gracie Peterson’s “Rivoli” shows helped purchase tables emblazoned with the college tartan.

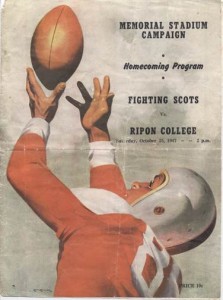

The return of intercollegiate athletics was eagerly embraced, and plans for a new football stadium in memory of men who served in the two world wars were unveiled. Like the student union project, this became a popular fundraising cause.

Everywhere, people were rushing to put memories of the war behind them and get on with their lives in the promise of a new peaceful era. Back in Japan, Takashi Komatsu was appointed to oversee the mammoth job of salvaging destroyed war materials and rebuilding Japan’s shipbuilding industry. Makoto Tsuda—Slurpy—went to work for him, prior to entering a prosperous career with the Noritake Company. In the fall of 1948, Komatsu’s sons, William and Mark, enrolled as freshmen at Monmouth College.

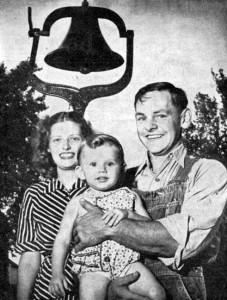

Medal of Honor recipient Bobby Dunlap was happy to return to a life of farming after the war with his wife, Mary Louise ’45, and daughter, Donna.

In his book, “The Greatest Generation,” Tom Brokaw sought to explain why the men and women who brought America through its greatest conflict spoke so little of their experiences in the war; why heroes like Bobby Dunlap remained modest until the end. “They have so many stories to tell,” he wrote, “stories that in many cases they have never told before, because in a deep sense they didn’t think that what they were doing was that special, because everyone else was doing it too.”

That probably summed up Bobby Dunlap’s philosophy. The hero of Iwo Jima was just happy to return to his hog farm.