The fraternity brothers who lived in the Tau Kappa Epsilon house at the corner of 6th and Broadway protected their Japanese-born member Makoto Tsuda from being sent to a relocation camp until his graduation in 1943.

(Second in a three-part series about Monmouth College’s involvement in World War II.)

December 7, 1941, dawned cold and blustery with the smell of snow in the air. As was often their habit, several brothers from Tau Kappa Epsilon left the warmth of their comfortable house on East Broadway for a Sunday afternoon outing at the Rivoli Theater. The show that day was “A Yank in the RAF,” starring Tyrone Powers and Betty Grable in a “realistic reproduction of the heroic evacuation of Dunkirk.”

Following the movie, the boys stopped off at Carter’s Pharmacy on Broadway for a Coke. The radio behind the fountain was tuned to WGN and the announcer said that some unknown planes had attacked Pearl Harbor. Makoto Tsuda, who was one of Tekes listening, was filled with dread, suspecting immediately that the unknown planes were sent from his native country.

That evening, President Grier came to Tsuda and told him, “You are under my protection.” Grier had been in contact with U.S. government officials and assured Tsuda he was safe. He then made two requests: First, Tsuda wasn’t to leave the Monmouth area, and second, he wasn’t to go anywhere, except on campus, without being accompanied by friends. A grateful Tsuda said later it was the action of Grier that kept him from being sent to a concentration camp in California. He was also grateful to his fellow Tekes, who went out of their way to protect him. The only contact he would have with a governmental official until his graduation was a visit from a local law enforcement official who asked if he had either a shortwave radio or a camera. Because he had neither, the official left. After graduating in the summer of 1943, Tsuda was reluctantly forced to return to Japan, where he was drafted into the Japanese army as a cryptographer. Not knowing that Tsuda was not assigned to combat, fellow Teke Harley Bergstrand ’46 would later note that whenever brothers stationed in the Pacific went into battle, they would say a little prayer that they would not be shooting at Slurpy.

Senior class president Bobby Dunlap ’42 admonished his fellow students to get in shape to prepare for the war effort.

Every student who was at Monmouth College on Sunday, Dec. 7, also remembers vividly the chapel service the following morning, when a radio was placed on the stage and the entire assemblage listened intently to President Roosevelt addressing a joint session of Congress. The address began with the immortal words, “Yesterday, December 7th, 1941—a date which will live in infamy…”

With war officially declared, President Grier attended a meeting of college administrators in Baltimore, where a strategy was adopted for accelerating class schedules to allow young men to enter the service more quickly. At the morning chapel on Jan. 8, 1942, he announced that under the new schedule, juniors could graduate the following January, sophomores in August of ’43 and freshmen in three years. Summer school, of course, would be a major component of the plan. In that spring of 1942, men began enlisting in the reserves in great numbers. Even so, one of the most influential students on campus, chided his fellow classmates.

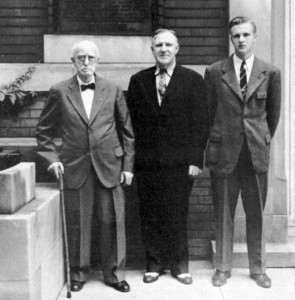

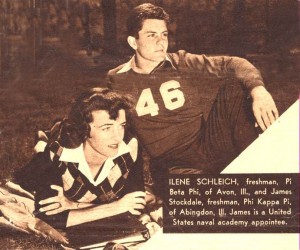

Future Medal of Honor recipient and vice admiral Jim Stockdale was photographed on campus his freshman year, prior to transferring to the Naval Academy.

Bobby Dunlap, president of the senior class, a standout quarterback, and a future Marine hero, said, “I don’t think we’re taking the war seriously enough on campus. I think fellows should attempt to get in shape to meet the physical requirements of our democracy.”

One student who was taking the war seriously was Dunlap’s cousin, Jim Stockdale. The freshman from Abingdon had already been accepted for admission at the U.S. Naval Academy, where he would graduate in 1946 and become a decorated pilot, a Medal of Honor winner and vice admiral of the Navy.

Just as their fathers and grandfathers had in earlier wars, other Fighting Scots were also rallying to the cause. A case in point was Robert Barnes ’45, who elected to enter the Army Signal Corps. His father, Wallace Barnes, Class of 1904, had served in the Spanish-American War, and his grandfather, Dr. J.A. Barnes, Class of 1870, was a Civil War veteran.

By the fall of 1942, the number of male students on campus had dropped to an alarming level. Realizing that something had to be done soon, business manager David McMichael and President Grier visited Navy officials in Washington to see if Monmouth College might become home to a unit of WAVES. Within a short time, officers visited campus and were delighted with the dormitories, gymnasium, meal facilities and classroom space. On Dec. 10, a Navy telegram arrived, notifying college officials that it would be sending not WAVES, but 600 pre-flight cadets. The college was given only until Jan. 7 to be ready to receive the first unit of 250. With Christmas vacation beginning Dec. 18, the next few weeks would be hectic.

When notice was given that the Navy was coming to campus, women students did not have much time to move out of the dorms and into the fraternity houses. Most of their belongings were moved by sled.

The three fraternity houses were overhauled, with all furniture and personal belongings removed, sometimes by sled; the Music Department was moved out of the Fine Arts Building; Marshall Hall, which had been vacant, was put into shape; the three dormitories were cleared of 190 female students who were sent to live in off-campus housing, including the three fraternity houses—Teke, Phi Kap and Theta Chi. The faculty declared a moving day and classes were cancelled so the women could gather up their gear. McMichael Hall was made ready to receive 250 cadets and its kitchen was transformed into a galley to serve 600 cadets in an hour or less. In the brand new Grier Hall, a sick bay was established to accommodate 24 patients under the care of three nurses and three doctors, and an electric elevator was installed to accommodate storage in the attic. Cadets told time by a ship’s bell, mounted by the Grier entrance. A commissary, or Gedunk, was established in Grier’s lower level. There, cadets could purchase such items as candy, newspapers, cold drinks and even condoms!

East Hall, or Sunnyside, was overhauled to hold 110 men and a naval office. Wallace Hall was completely revamped to include classrooms on the third floor, the naval office and a cadet post office.

The last week in December, 14 Monmouth faculty members and one trustee attended William Jewell College in Missouri to take a seminar in navigation. On Jan. 10, the college began instruction with about 20 teachers, no textbooks and little classroom equipment.

When the first platoon arrived at the train depot, they marched through Monmouth in civilian clothes to quarters that were not quite ready. Many slept on mattresses on the floor. Dishes for the mess were borrowed from the First and Second Church. The Monmouth armory furnished cots and blankets. It was not until six months later that the official Navy textbooks would see publication.

Coordinating the instruction for the college was math professor Hugh Beveridge, chosen for the role because of his experience as a cadet in the Student Army Training Corps at Monmouth College during the first World War. He was in charge of a faculty of 40 that included such MC faculty as Garrett Thiessen and Lyle Finley in the physical sciences, but also professors teaching outside their disciplines, such as speech professor Jean Liedman and philosophy professor Sam Thompson teaching Navigation. Bible professor Dales Buchanan taught Principles of Flight, which his daughter Dorothy said was ironic because he had only flown once. Yet he told his students if they had any questions he would find out the answer, and they respected him for it.

A number of Monmouth citizens also filled in as instructors. One such colorful character was Ralph B. Eckley ’23, chosen to teach “Theory of Flight” because of his long experience as a private pilot.

The “Yellow Peril,” an NP-1 Spartan trainer from Glenview Naval Air Station, was assembled on the front lawn of Grier Hall to help familiarize pre-flight cadets with the parts of an airplane.

Eckley immediately noticed that many of the French flight terms such as aileron, fuselage and empennage, were not comprehended by the cadets, many of which had never seen the inside of an airplane. So he asked the lieutenant in charge to contact Glenview Naval Air Station to have a retired NP-1 Spartan trainer flown to Monmouth to be used as an exhibit. The pilot who flew the plane to the Monmouth Airport, however, left it with an empty tank, so Eckley purchased five gallons of gas at the Phillips 66 station and enlisted the help of state police and sheriff’s deputies to taxi the plane along Sixth Street to East Broadway, where it was parked in front of the flagpole. Eckley reported to the skipper that he had broken a lot of regulations to get the plane there. The skipper replied that the order had been to get it on campus before sundown, and Eckley had met that directive. The plane, dubbed “The Yellow Peril,” was later moved to the front lawn of Grier Hall, where it would become a fixture throughout the duration of the pre-flight school.

Ralph Eckley ’23, an avid local pilot who served as an NFPS instructor, helped convince the Navy to adopt curriculum developed by Monmouth College faculty for its pre-flight training.

Later, working as a physics lab assistant under Lyle Finley, Eckley noticed that the 22 mimeographed experiments furnished by the Navy were inaccurate. He asked Finley for copies of experiments he used for his freshman students and had them run off on good bond paper. It wasn’t long before the Navy learned the syllabus was not being followed, and they sent a lieutenant commander to investigate. It was quickly apparent that the Navy’s experiments were inferior to Finley’s, so enough copies were run off for the Navy to use in six other colleges and universities. Monmouth College received a Naval citation for the curriculum improvement.

Life as a cadet was rigorous. Most of the Plebes, as they were called for the first four weeks, entered pre-flight school directly from civilian life. Reveille was sounded at 5:45 each morning and classes began at 7:30. Except for 90 minutes of physical training, the day was spent in classes—seven hours a day, six days a week. Following lunch, classes resumed until 5:30. Two hours each evening were set aside for study, leaving about an hour after dinner and 15 minutes before “Taps” at 9:45 as the only free time. Studying and sleeping was in itself difficult, as usually four to six cadets shared a single room. If course averages dropped below passing or if there were disciplinary issues, cadets lost their weekend privileges and had to report to study hall.

Those with weekend privileges could attend a dance in the gym each Saturday night, movies downtown, or recreation rooms at the American Legion and local lodges. They were also allowed to travel within a 50-mile radius, which meant soirees to the big cities of Galesburg, Rock Island and Burlington.

Watching the cadets became a popular pastime, not only for coeds, but also for members of the Monmouth community, who turned out each evening at 7 to watch the lowering of the colors. Huge crowds from the town also attended the regimental reviews, staged on the athletic field in honor of departing battalions.

Intercollegiate athletics, of course, were sidetracked by the war, but that didn’t mean Monmouth suffered from complete withdrawal. Although Bobby Woll ’35 was the sole remaining coach on campus, he would not be deterred. His 1943-44 basketball team, which included four Naval cadets, won nine of 11 games and was defeated only by Iowa and Camp Ellis. Naval cadets such as Bob Weaver of Ashland, Oregon, received Monmouth letters. The Navy also brought some sports VIPs to campus, including Wisconsin All-American grid star George Paskvan, former Missouri head coach Don Faurot and Cornelius Warmerdam, the world pole vaulting champion, who vaulted 15’8-1/2′ using a bamboo pole.

Female cast members in Gracie Peterson’s 1944 musical “Girl of the Year” had to make do with cardboard cutouts as dancing partners.

The coming of the Navy was particularly good news to Monmouth coeds, who had previously been used to having two boys to every girl. Although the cadets’ free time was extremely limited, they interacted socially with the coeds, and hosted four Navy proms each year. But the women also did their fair share for the war effort, organizing book drives for soldier barracks, selling stamps and bonds, collecting scrap metal and taking first aid courses. A number of women continued the tradition of the popular “Gracie Peterson” shows, although cardboard men had to be employed. The 1944 spring production, “Girl of the Year,” went on the road to Camp Ellis, where it was viewed by 2,000 enthusiastic soldiers.

Mary Fernald ’42 (right) lost both her hands in an accidental explosion at the ordnance plant where she worked.

Some Monmouth women were not content just to remain on campus. Professor Dorothy Donald took a leave of absence to perform war work. A handful of women students enlisted in the WAVES, WAACS and Red Cross. Mary Fernald, who went to work as a lab technician in the Kankakee Ordnance plant, suffered the loss of both hands in an explosion.

The women who did remain on campus did their best to maintain an air of normalcy. Rather than complaining about cramped conditions, seniors quartered in the former music studios of the Fine Arts Building pretended they were in a sorority and dubbed their house Phi Alpha Beta. And because there were no freshmen or sophomore men available to compete in the annual pole scrap, the women of those classes instead instituted a tug of war. Adding to that spectacle was the use of a fire hose by members of the Pep Club.

Crimson Masque director Ruth Williams, determined to keep theater alive at Monmouth, partnered with a community theater group, and four excellent dramatic productions that included both faculty and townspeople, were still offered each year in the Little Theatre.

The pre-flight school lasted 18 months at Monmouth. It was succeeded in July 1944 by a Naval Academic Refresher Unit (V-5). These men were experienced bluejackets from the fleet desiring to enter pre-flight directly for training as Navy pilots. Subjects taught were math, physics, English, history, Naval organization and physical education.

By early 1945, with the war having been won in Europe, members of the campus community eagerly awaited word of an Allied victory in the Pacific. In late February, they read of a desperate battle on the volcanic islands of Iwo Jima, in which one of their own was a key player. Bobby Dunlap, a farm boy from Abingdon, had enlisted in the Marine reserves while still a student. Called “the biggest little man on campus,” the 5-foot-9 quarterback was actually offered a contract by the Philadelphia Eagles, but he was called up by the Marines before training camp began. Putting his quarterback skills to good use, he nevertheless became a seasoned Marine Corps captain and fought bravely at Guadalcanal, Guam and Bougainville. On Feb. 19, as a member of the 5th Marine Division, he led 285 men onto Iwo Jima, fewer than half of whom would be alive after the first four days of fighting. Defying uninterrupted blasts of artillery and machine gun fire, Dunlap led his troops in a determined advance toward steep cliffs on the island. He crawled alone 200 yards forward of his front lines, located enemy gun positions and relayed the information to supporting artillery. For eight days he hardly slept, and he had taken out dozens of Japanese pillboxes when he was finally shot in the hip by a sniper. He would spend the next nine months in a full body cast. For his gallantry, President Truman presented Dunlap with the Medal of Honor on Dec. 18, 1945, in a White House ceremony.

In the four years of conflict, Monmouth College sent more than 700 of its students, faculty and alumni to all regions of the world. Of these, 43 made the supreme sacrifice.

(Concluded in next installment)