At the suggestion of historian and veteran blogger Stacy Cordery, I have decided to turn a 2005 presentation I gave marking the 60th anniversary of the end of World War II into a blog. Specifically, the presentation focused on Monmouth College’s involvement in the war.

In this first of three parts, I describe the prologue to war on the Monmouth campus.

Takashi Komatsu ’10 would become a leading Japanese industrialist who played a key role in Japanese political affairs in the years leading up to World War II.

In 1900, a Presbyterian missionary walked into a curio shop in Northfield, Mass., and struck up a conversation with a young Japanese boy who was running the store. The boy, Takashi Komatsu, was just 14 years old and had recently emigrated alone from Japan. He was very intelligent and ambitious but lacked the funds to advance himself or his education. Quite taken with his story, the missionary wrote her sister, Mrs. W.W. McCullough in Monmouth, Ill., to see if Komatsu could come live with the McCulloughs, who ran a Monmouth lumber yard, and enroll at Monmouth High School.

Rooming with the McCullough family in their home on East Second Ave., a young Komatsu enjoys a picnic on their front lawn.

Komatsu thrived in Monmouth, was valedictorian of his MHS class and entered Monmouth College, where he became a champion debater. Graduating from the college in 1910, he studied international law at Harvard before returning to Japan, where he considered becoming a Christian missionary. Instead, he tutored the grandchildren of a Japanese steamship magnate, leading to a job as his private secretary. By the age of 35 he was a steamship executive himself, carrying on his work against a backdrop of growing militarism in Japan.

The Great Depression had wrecked Japan’s foreign markets and with the population increasing dramatically, the government began to consider expansion through military conquest. When Japan occupied Manchuria in 1931, Komatsu was sent to the U.S. on a three-month speaking tour to defend his government’s actions.

Komatsu (left) meets with President Grier during his 1940 visit to the U.S. to attend the New York World’s Fair.

In 1940, with relations between Japan and the United States rapidly deteriorating, Komatsu again visited the United States as a special commissioner representing Japanese exhibitors at the New York World’s Fair. Invited by Monmouth College president James Harper Grier to address the alumni banquet at that summer’s commencement, he expressed hope that Japan and the U.S. could reconcile their differences. The United States, he said, had played a significant role in bringing Japan into the world picture and for this reason should look with kindness upon Japan. The following day, Komatsu was presented with an honorary degree by his alma mater, as was the commencement speaker, Charles Sprague, who had been Komatsu’s classmate and was then governor of Washington State. They spent that night at the home of President Grier discussing the worsening conditions between the two countries.

Returning to Japan, Komatsu was called to report to government circles as a long-time expert on America who had recently visited the country. He told officials Japan should not join Italy and Germany; he said that Japan’s problems with America could be peacefully negotiated; he said war with America would be disastrous for Japan. It was not what they wanted to hear, and he was not allowed to speak in public thereafter. The Japanese government felt the need to expand shipping facilities for the war effort and took control of Komatsu’s ship building company, which it merged with one of the country’s largest steel companies and made Komatsu its director general. But because of his outspoken stance against the war, he would remain under suspicion and close scrutiny.

Robert Black ’41 was the first Monmouth College student to enlist in the military during World War II as well as the first student killed.

As the school year got under way that September of 1940, the Monmouth College campus was abuzz with talk of war. Under supervision of the physics department, a flight school was organized at Monmouth Airport. On Oct. 16, Robert Black, a junior from New Mexico, became the first MC student to register with the Warren County Selective Service Board. A year and a half later, he would also become the first Monmouth graduate to die in the service, as his twin-engine Army training plane crashed in California.

Socialist politician Norman Thomas, an avowed anti-war activist, spoke at Monmouth College in 1940 about the role of the United States in world politics.

In December, President Grier invited the well-known Presbyterian minister and Socialist presidential candidate Norman Thomas to lecture on “America’s Role in World Affairs.” Speaking to a capacity crowd in the Auditorium, Thomas pointed out the obvious danger that Nazi Germany had become, but warned against unreserved support of Great Britain, lest the old system of colonialism and capitalism be revived. America’s role, he said, should be to use her influence to create the kind of post-war world it desired.

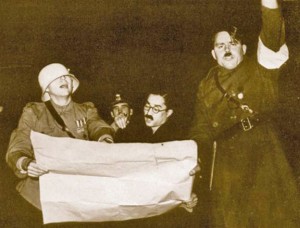

From left, students Corky Kirkpatrick, Makota Tsuda and Ted Winbigler portray the three Axis leaders in a 1941 chapel skit.

A memorable chapel skit in the spring of 1941 featured Ted Winbigler ’41 as Hitler and Corky Kirkpatrick ’42 as Mussolini in an irreverent spoof of an Axis leaders’ meeting. Portraying Japanese foreign minister Matsuoko in the skit was a sophomore international student from Japan named Makoto Tsuda, or, as he had been nicknamed by his Teke fraternity brothers, “Slurpy.” Slurpy had come to Monmouth College in the fall of 1939 as a Bancroft Scholar. The scholarship fund was administered by the Japan-America Society, which counted as one of its members none other than Monmouth College’s first Japanese student, Takashi Komatsu.

As rumors of America entering the war began to intensify, President Grier issued a letter in May 1941 to all MC male students. The letter urged students not to interrupt their studies and noted, “We must not permit tension of the times unnecessarily to disrupt normal procedures.”

Carl Sandburg, speaking at Monmouth prior to Pearl Harbor, was a proponent of the U.S. entering the war.

On Oct. 23, 1941, the noted poet and Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg presented a concert in the Auditorium. Sandburg, an unabashed flag-waver and a veteran of the Spanish-American War, blamed the condition and inactivity of the United States on the current generation’s propensity for comfort and convenience, and said that only by returning to the trial-and-struggle theme of the pioneers could America again become a world leader. Sandburg’s words would prove prophetic six weeks later, as after that date, trial and struggle would occupy America for the next four years.

(Continued in next post.)