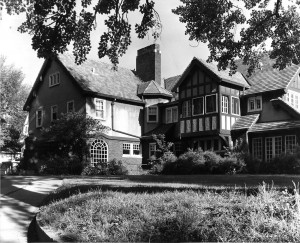

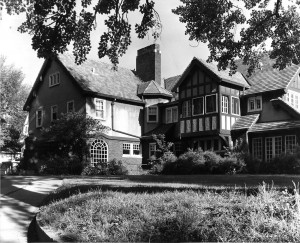

A front view of the Brown house when it still retained such original features as wooden shutters, a pillared entry and ivy-covered walls.

Standing high on the corner of Broadway and Sixth Street for more than a century, the Tudor revival house that today serves as headquarters for Monmouth College admissions has a history that is both colorful and tragic.

Constructed as a residence in 1912 by attorney John Burrows Brown, the house was designed by the prominent Peoria architectural firm of Hewitt & Emerson, which had also produced plans for Monmouth College’s Wallace Hall and Carnegie Library. It was built by Monmouth’s premier contracting company of the era, Apsey and Fusch, for the princely sum of $60,000, an amount which in today’s currency would translate to more than $1 million.

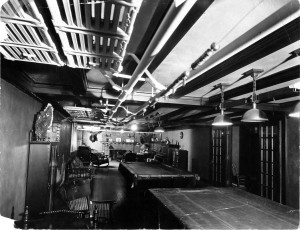

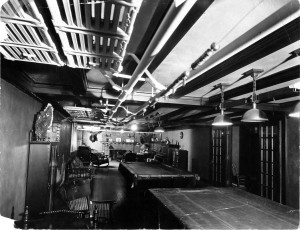

The long and narrow basement game room contained two billiard tables, a piano and a fireplace.

Although designed in the style of a rustic English cottage, the home also exhibits some Midwestern Prairie-style influences. Among its most unusual features were a basement containing a 60-foot-long game room, laundry room, food storage pantry and wine cellar; five fireplaces, three full bathrooms and two half-baths; and a large detached two-stall garage in the rear with quarters for the family chauffeur. A driveway from Broadway passed under a porte cochere on the east side of the house and led to a service court, from which a second driveway led to Sixth Street.

The orignal entry foyer for the Brown home now serves as a reception area for the office of admissions.

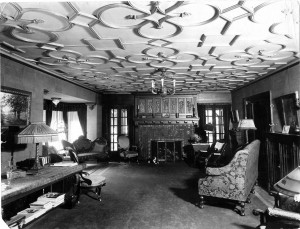

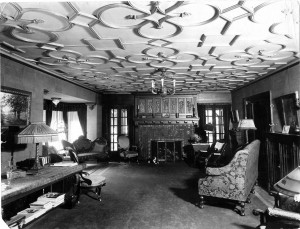

The main floor featured a central hall with stone fireplace and ornamental plaster ceiling. Flanking both sides of the hall were French doors leading to a reception room, a library with elaborate casework, and a dining room with a built-in sideboard. Adjoining the dining room was a large breakfast room opening onto a side porch. A service wing, located north of the grand stairway, contained a modern (for 1912) built-in kitchen, a cold pantry, a servants’ hall and a telephone room.

Probably taken in the 1920s, this view of the library shows off the dramatic cast plaster ceiling, designed by architect Herbert Heweitt.

The central stairway contained a landing with a window seat and three art glass windows. At the top of stairs was a spacious upper hall surrounded by a master bedroom with a vaulted ceiling, a guest bedroom, and a bedroom for Brown’s widowed mother-in-law, Irene Eldridg Smith, who boarded with the couple. That room featured a fireplace and a private balcony. There was also a spacious sitting room overlooking the front entrance, a sleeping porch tied to the master bedroom, and a family bathroom.

An upstairs north wing contained a sewing room, guest bathroom, servants’ bathroom, service hall and two servant bedrooms.

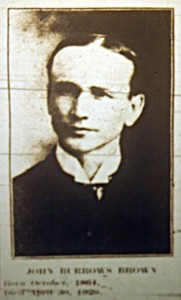

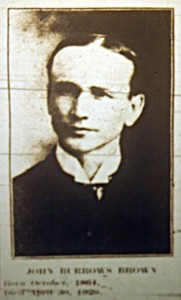

The builder, John B. Brown, was born in 1864 in Connecticut and moved with his parents to Whiteside County, Illinois, in 1868. He graduated from Knox College, studied law and was admitted to the Illinois bar in 1899. The following year, he married Edna Bell Smith, daughter of one of Monmouth’s leading druggists.

A rather plain farmhouse–the home of Professor Alexander Young–originally occupied the corner where John Brown built his residence.

In 1905, while living in his wife’s hometown of Roseville, Brown purchased the property on which the house would eventually be built. (A previous house on the site, built in the 1860s, had been the home of Alexander Young, Monmouth College’s first professor of Greek and Hebrew.)

Brown was the senior member of the Monmouth law firm of Brown & Soule, with offices in the Patton Block. His partner, Melville G. Soule (Monmouth College class of 1897), was the first cousin of his wife, Edna. Both Melville and Edna were the grandchildren of William F. Smith, one of Monmouth’s first settlers, who opened the town’s first variety store in 1835. Brown & Soule in 1918 consolidated with the firm of Safford & Graham to form Brown, Safford, Graham & Soule.

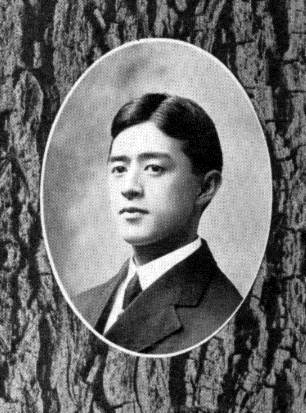

John Burrows Brown (1864-1920)

Because of his brilliant mind, John Burrows Brown became one of the most prominent attorneys in western Illinois. He was an ardent Republican who supported William McKinley in the heated campaign against William Jennings Bryan, and made several speeches supporting the gold standard platform. He was a candidate for the Illinois Supreme Court, and also delivered the address at the cornerstone laying for the new Monmouth Hospital. He was a trustee of Knox College, president of the Warren County Bar Association, and a member of the Monmouth Country Club, Commercial Club and Elks lodge.

An early view of the back yard of the Brown house, before the annex was built and a parking lot constructed.

The Browns moved into their new home in 1913. They likely initially had three live-in servants, as quarters had been built for a chauffeur in the garage and two servants in the house. While the Browns were part of Monmouth society, they continued to play an active role in Roseville, particularly in the Congregational Church where they were members, and the Library Association, of which Edna was the first president.

John and Edna both suffered from poor health, and in they spent the summer of 1919 in Waukesha, Wis., with Mrs. Smith and a niece, which proved beneficial to both of them. They were planning to go south for the winter, but in October, Edna contracted a cold and rapidly declined. On Nov. 2, Edna Brown died at the age of 52. Her funeral was held at the Brown home and she was buried in the family plot in Roseville Cemetery.

A view of the Brown house in winter, probably during the early ‘Teens, judging from the carbon arc streetlamp and the interurban track running in the middle of Broadway.

John Brown continued to share the home with Edna’s mother, but by the next spring, his depression over his wife’s death and his own poor health were making him increasingly restless and nervous. On the night of Friday, April 30, 1920, he came home right before the supper hour and dined with his mother-in-law. He retired to his room at 7:30, and Mrs. Smith, thinking he intended to go to bed, remained downstairs. Shortly after 8, she heard a muffled report, but paid no attention. Around 10, she retired to her own bedroom, next to Brown’s, and seeing a light under the door, looked in to see if he needed anything.

She discovered Brown’s lifeless body at the edge of his bed and between his feet was a .405 caliber rifle. Mrs. Smith immediately called her nephew, Glenn Soule, who lived further down Broadway, and he contacted Coroner Ralph Graham. Soule, Graham and next-door neighbor I.S. Smith met at the house and proceeded to the bedroom where they determined that Brown had taken the rifle from the closet, sat on the edge of the bed, and placed the gun between his feet with the barrel in his mouth. He had previously removed the shoe and sock from his right foot and he had tripped the hammer with one of his toes. The bullet went through his head and into the ceiling. Coroner Graham called an inquest for the following evening, and the jury immediately concurred with the above findings. Brown’s funeral, held in the home the following Monday, was widely attended and burial was next to his wife in Roseville Cemetery.

Glenn Soule was the last owner of the house before it was purchased by Monmouth College. He was the first cousin of John Brown’s wife, Edna.

Brown left the home to his law partner, Glenn Soule, with the provision that Mrs. Smith would continue to live there the rest of her life. Soule and his wife, Etha, moved into the house later that year.

Mrs. Smith survived nearly another decade, finally passing away just before Christmas, 1929. In her will, Mrs. Smith left the college $25,000 as a memorial to her father, Truman Eldridg, who had been one of Monmouth College’s first trustees. In 1931, the college used the bequest as partial payment on the house, which it purchased for $35,000 from Soule. Included in the sale were most of the home’s furnishings.

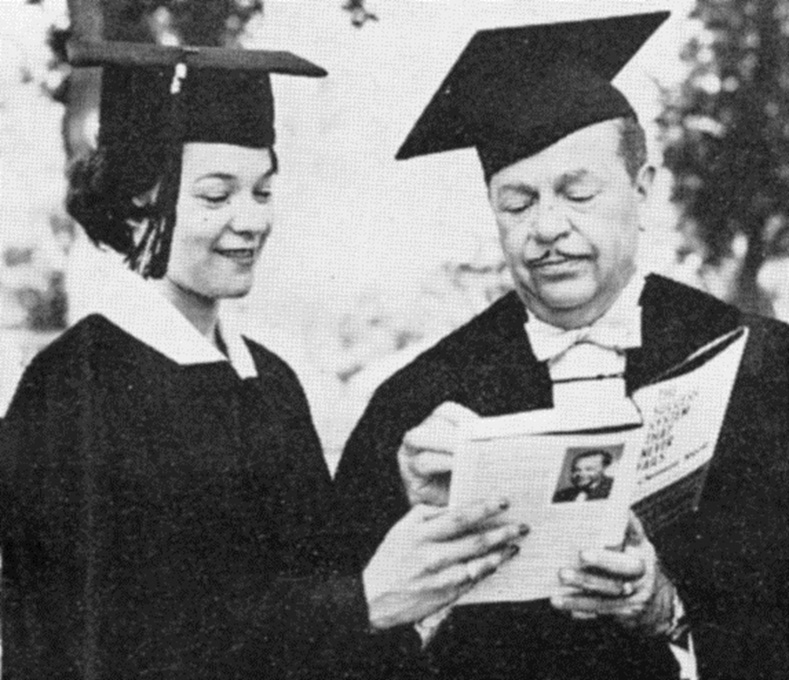

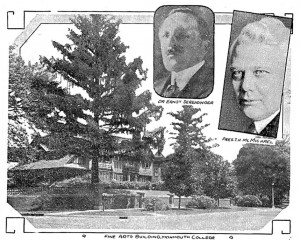

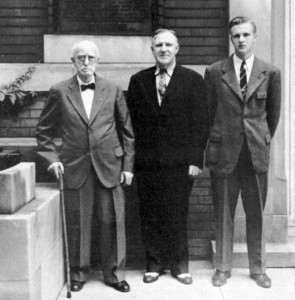

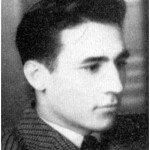

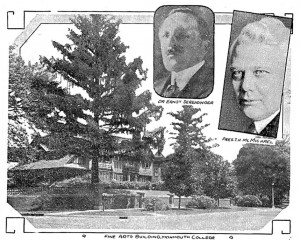

Ernst Derendinger, a native of Switzerland, served as the first head of MC’s new Fine Arts Department.

The college immediately converted the building to house its new Fine Arts Department, recently endowed by architect Dan Everett Waid (MC 1887), in memory of his wife. Dr. Ernst Derendinger, a native of Switzerland, who had studied art in Germany and written a book on art history, had been hired the previous year to oversee the Fine Arts Department. His idea was to develop a curriculum for the appreciation of art based on one at HarvardUniversity. (At the invitation of the Carnegie Foundation, he had spent the previous two summers doing research at Harvard on the teaching of art appreciation.) Monmouth’s program started out with a gift of 200 art books from the Carnegie Foundation, along with 1,500 slides and 1,500 photographs, with plans to add an additional 1,500 slides each year until the collection had reached a total of 10,000.

The original front porch of the Fine Arts Building featured stucco columns supporting a wooden pergola.

An apartment for Derendinger and his wife was created on the second floor, and offices for Derendinger and his assistant, Harriet Pease, were established on the main floor. (Miss Pease would serve as art assistant and librarian throughout the entire life of the Fine Arts Building, from 1931 until 1958.) Derendinger turned the former game room in the basement into an art lecture hall and fitted it out with a newly purchased stereopticon lantern and screen.

Professor Tom Hamilton teaches an art seminar in the library.

After just two years, Derendinger left Monmouth, and was succeeded in the post by Thomas Hamilton. A 1907 MC graduate, Hamilton was hired to direct the Conservatory of Music, but also served as acting professor of the appreciation of art until 1939, when he became a full-time professor of art appreciation. His wife, Martha, joined him in the department in 1937, teaching constume design, household management, and the history of furniture and decoration. The Hamiltons occupied the upstairs apartment from 1932 until 1939. Orchestra director Gail Kubik also lived in quarters on the second floor for part of that time.

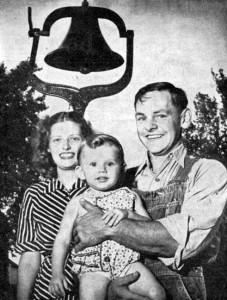

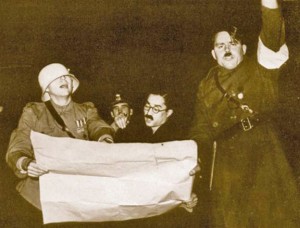

The Loya family stands on the west lawn of the Fine Arts Building, where they lived in an upstairs apartment from 1939-1941.

When the Hamiltons built a new house in their Brewery Hill subdivision in 1939, new music professor Hal Loya and his wife, Eileen, moved into the apartment, which they occupied until 1941. During that time their two children were born. Mrs. Loya fondly recalls the cramped quarters in the apartment (their kitchen was the former servants’ bathroom) and how grateful she was when the college increased Hal’s salary so they could afford to rent a house. Many alumni have fond memories of taking piano lessons from Edna Riggs and Gracie Peterson in their studios on the second floor.

The master bedroom of the Brown house, with its vaulted ceiling, became a home to coed students during World War II, when naval cadets occupied the dormitories.

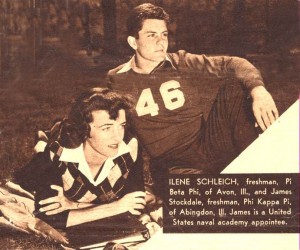

During World War II, the music department was moved out of the upstairs and it was converted to a dormitory for senior women, who had been displaced on campus by Naval cadets. Mary Louise Winbigler, a 1938 MC graduate and admissions secretary, served as the resident house mother. The girls dubbed their “sorority” Phi Alpha Beta. Following the war, the music department reoccupied the second floor and Edna Riggs lived in the apartment there for a time.

Both students and townspeople took piano lessons from Edna Riggs in her private studio. located on the second floor of the Fine Arts Building.

In 1957, the college trustees saw a need to expand available space in Carnegie Library and authorized relocating administrative offices from the library and the Woodbine to a centralized location in the Fine Arts Building. Business manager Harlan Cain prepared a detailed plan to convert the building into offices. In the spring of 1958 the music department vacated the second floor and relocated to Austin Hall.

During the summer of 1958, the Woodbine was renovated to accommodate the art department, while major renovations were carried out in the Fine Arts Building. The most significant change was the construction of an annex connecting the original home with the garage to the north, providing room for the business office, physical plant and office services.

In 1957, an annex, linking the house with the garage, was constructed to house the business office.

The president’s office was moved into the house’s former living room and dining room, with the academic dean across the hall. The alumni and public relations offices were moved to the second floor, and admissions to the basement. A darkroom for the college photographer was installed in the old basement pantry. A new centralized switchboard system was also located in the building.

A college board meeting is held in the former game room of the Brown house in the early 1960s.

When Hewes library was completed in 1970, the dean of students offices were moved into the old Carnegie Library. Admissions and financial aid were moved to the former Sigma Phi Epsilon house next door to the Administration Building. This left the academic dean and registrar on the second floor of the house, data processing and the alumni office on the first floor, and college relations in the basement.

By the early 1980s, the former president’s home across the street from the Administration Building (known as The Manor), was converted to offices for alumni and college relations, leaving the president, academic dean, admissions, registrar, business office and physical plant in the Administration Building. In 1986, President Haywood decided to move the president’s office into Wallace Hall, freeing up the house’s most elegant public rooms for use by the admissions office.

When the former Carnegie Library was converted to Poling Hall in 1996, the business office, physical plant and registrar relocated there, leaving the Administration Building’s second floor and basement vacant. College relations then occupied the second floor and college communications occupied the basement, leaving the entire main floor for use by admissions.

A complete renovation of the basement of the Brown house was undertaken in the summer of 2011.

Recent renovations to the building included the construction in 2000-2001 of a new front entrance and the removal of the driveway leading to the porte cochere. In 2008, the former kitchen (which later housed the business office and vault) was converted to restrooms, the entire basement was extensively remodeled and a new HVAC system was installed. In 2011, the “annex,” which had connected the main house to the garage, was razed, as was the garage, to make room for the Center for Science and Business. A new handicapped-accessible rear entrance was constructed in its place.

It is estimated that replacing the building today would cost $164 per square foot. At more than 10,000 square feet of space, that would mean about $1.78 million. Today, the former Brown house is one of the jewels of the Monmouth campus, and is one of the oldest buildings—behind only Quinby House, Marshall Hall, Poling Hall, McMichael Academic and Wallace Hall. As the first stop for prospective students and parents, it serves as impressive and comfortable welcoming center.